Photo: An iconic photo of former conservative party chief Kim Mu-seong in Busan during his public quarrel with then-president Park Geun-hye over party slate-setting, c.2016. Credit: Facebook page of Kim Mu-seong.

In a democracy, the raison d’etre of a politician is to win elections. In South Korea, most politicians run under the banner of one of the two major parties (currently, the People Power Party 국민의힘 and the Democratic Party 민주당) and, for the most part, voters tend to vote along party lines rather than closely examining the individual candidates. This means that setting the slate of candidates to run in an election, in a process called “gongcheon 공천”, or “public recommendation”, is arguably the most important function of a political party in South Korea.

To encourage self-governance on the part of political parties, South Korea’s election laws impose only a minimal set of requirements for setting the party slate. A political party may only run one candidate per electoral district. No money or benefits may exchange hands for the purpose of selecting a candidate. And, barring a narrowly defined set of exceptions, a party may not cancel or change candidates once selected. Other than these requirements, parties have carte blanche in selecting who may run as a candidate, and how they may be selected.

In the early days of South Korean democracy, this flexibility often led to a “boss politics 보스 정치”, in which outsized personalities like Kim Young-sam 김영삼 and Kim Dae-jung 김대중 created personality-driven parties filled with legislators who were personally loyal to party leaders. The concentration of slate-setting power also led to rampant bribery and influence peddling, despite formal prohibitions.

Because of its centrality to the political process, the party slate is the main battlefield of intra-party factions and an endless source of drama, especially when an incumbent loses his or her place on the slate. In 2000, for example, then-conservative Assembly Member Kim Ho-il 김호일 punched his party’s own director-general 사무총장 - in public and in front of cameras - after failing to make the party slate. In 2008, 24 liberal lawmakers who failed to make the cut for the party slate held a street protest against their own party, with Assembly Member Seol Hun 설훈 occupying the party offices for a hunger strike.

In response, both major parties have implemented significant reforms in recent years, such as introducing primary elections or aptitude exams. (See previous coverage, “PPP Attempts Meritocracy.”) All the same, parties often choose for a variety of reasons not to hold a competitive intra-party selection process. In the 2020 Assembly Elections 총선, for example, the Democratic Party did not have a competitive selection process in 118 electoral districts, or 46.7% of the 253 total districts. Usually, the presence of a strong incumbent - either of one’s own party or from across the aisle - may discourage multiple challengers.

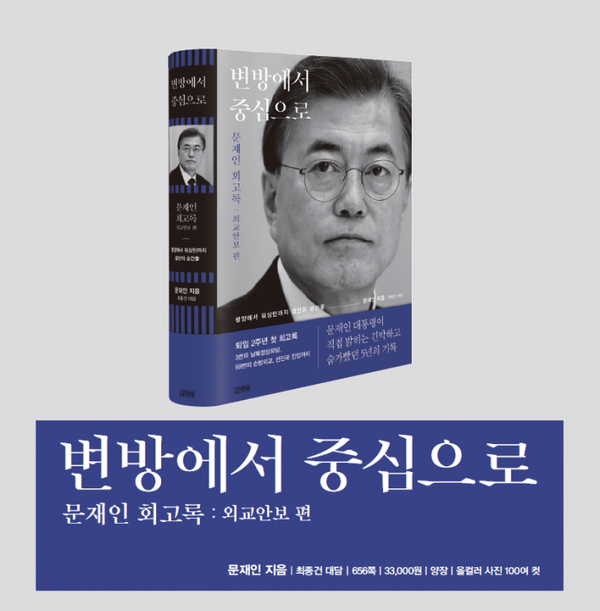

But in other cases, parties can make a “strategic recommendation 전략공천”, introducing a single, specific challenger in a high-profile race with the goal of benefitting the party’s overall election campaign. In the 2012 Assembly Election, the conservative party made a splash by having 27-year-old woman Son Su-jo 손수조 to run against future president Moon Jae-in 문재인, the biggest name among liberals at the time. Even though Son lost, the significant media attention given to her campaign went a long way toward burnishing the image of conservatives as future-oriented, contributing to conservatives’ hold on their legislative majority.

Presidential influence is a persistent issue in slate-setting for the ruling party. As a formal matter, the president is legally prohibited from participating in or influencing his or her party’s slate-setting process. But a party’s highest profile official naturally has a significant stake in who is elected as the party’s representatives, particularly if the president belongs to a minority faction within the party.

Both sides of South Korean politics offer dramatic examples of factional battles over slate-setting, centered around the president. In 2003, the main liberal party (at the time called Millennium Democratic Party 새천년민주당) split in two, as the faction of then-president Roh Moo-hyun 노무현 openly clashed with the former faction of Kim Dae-jung 김대중 in the run-up to the 2004 Assembly Election. The Roh faction went on to establish the Uri Party 열린우리당, while the remaining MDP legislators joined the conservatives in impeaching Roh. When the Constitutional Court 헌법재판소 rejected the impeachment petition, Roh’s Uri Party swept the Assembly Election, riding the wave of backlash.

On the other side of the aisle there is a similar story, with a less than happy ending. Kim Mu-seong 김무성, leader of the conservative party at the time (then called Saenuri Party 새누리당), took his party’s official seal and left Seoul, making it procedurally impossible for his party to finalize its slate ahead of the 2016 Assembly Election. Kim’s unauthorized excursion, which later came to be known derisively as the Royal Seal Incident 옥새파동, was an act of defiance against then-president Park Geun-hye 박근혜, who demanded that her party exclude from the slate up to 40 legislators not aligned with her faction.

The division within the Saenuri Party led to a disastrous loss in the Assembly Election, paving the way for Park’s impeachment and removal in 2017. For her intervention in the intra-party process, Park was prosecuted and sentenced to two years in prison in 2018.